Robert Radler has directed some iconic martial arts action movies including Best of the Best 1 & 2, Showdown and more; he stopped by The Action Elite to chat with Eoin and Alex about his career including projects he is working on now.

EOIN: We’re going to talk about some of your recent projects and then we’ll talk about the movies a little later. I was particularly interested in your TED talk on the S.S. United States. What made you want to do a TED Talk on it and how did that all come about?

Oh boy, if you get me started on the S.S. United States, I won’t talk about anything else (laughs). When I was a little kid, maybe six years old, my dad took me to New York luxury liner road, basically the west side of New York, where they still park these days. And I saw the Queen Mary, The Isle De France and the S.S. United States. I think it was maybe my first little glimpse of nationalism because the United States looked way better than those other ships. They were stately old ships to me, the United States with its swept back funnels and sharp bow looked like the future. It looked like it was going real fast just sitting there. So I started a lifelong kind of obsession with that ship. When I went back to graduate school at NYU for filmmaking, I had my motorcycle, I got on it. I went to the West Side a number of times and waited for that ship to appear. It was like a ghost in my mind seeing this beautiful ship.

It was my first job in the film business. I had just quit the NYU graduate school because we weren’t doing anything. I got a job through them, working for a documentarian named Gene Searchinger, who was a great guy and my mentor in a lot of ways. While I was working days on that on his shows, I was working nights on trying to get figure out what happened to the S.S. United States and there was no internet so you had to just make cold calls to the Maritime Administration, The United States lines, and so on, which no longer existed.

So gradually I got to the James River Reserve fleet and discovered that she was in Norfolk, Virginia, and I petitioned to film on her and they told me that she had just been dehumidified and you couldn’t get in there. It was a sealed ship. They’re going to leave it just the way it was. I tried and tried and tried. I mean, for months, I tried everything I could think of and I forgot about it. Then one day I got a call from them from the Maritime Administration, saying “the BBC is going to be down there in Norfolk. You want to film on the ship? We’re going to break the seals”. So I went down there and it turned out the BBC wasn’t there. But some of the imagery in Lady in Waiting is from that very day in 1975. The stills. Anyway, the movie footage I shot before everything inside was auctioned off. The movie footage was lost. I think my mother was doing house cleaning (laughs).

So from being a little kid on, I felt like I was the only person that remembered this great ship. It was so sad to see her sitting there behind a coal dock in Norfolk, all dirty. I thought that was as bad as a ship could look. Little did I know it had like 40 years on and she looks a lot worse. Anyway, when the internet started up, I discovered that there were other crazy people like me that remembered this ship and deified it almost because it’s the fastest ship in the world. Or at least that’s what they say. There are those who believe in people who really would know that she could go 60 miles an hour in her sea trials. She went 50, but with two thirds of the boilers lit and they never pushed her. But the man who was her caregiver, her keeper in the last few years (he’s gone now) assured me she could go 60 miles an hour, which is pretty incredible for a thousand-foot-long ship anyway.

Mark B. Perry is my partner on the Lady in Waiting film and one of the top guys in the S.S. United States Conservancy, along with Susan Gibbs, who’s the granddaughter of William Frances Gibbs, who designed the ship 75 percent of our ships in World War Two, America’s ships and I get in with them. Mark was wonderful enough to put in his own money for us to make this film. There’s actually been four films now on that ship, and I can tell you where the sequel is if you’d like to see the sequel of Lady in Waiting. It’s online called Made in America, and it’s on the Conservancy’s website. Right now, for the first time, there is another company, a development company called RXR, that is helping pay the holding costs of the ship. It’s like $700,000 a year, at least just for it to sit there. It’s hard to find a place to put a thousand-foot-long ship. In any case, we’re hoping that this group, since they’re putting money into it, is serious and that they will in fact turn her into a static attraction, probably in New York, but maybe somewhere else so that she’s not destroyed for the ages. There are very few real ocean liners left. That that would be wonderful.

EOIN: My dad was actually on it. I spoke to him about it the other day, and he used to work for Hertz Rent-A-Car and I believe it was in Southampton and going to the US. He said it was one of the fastest and most beautiful ships he had been on.

It was very utilitarian. There was no wood on it and because wood burns and ships sink. Mr. Gibbs was really fanatic about that. He tried to build an aluminum piano. He went to Steinway to build an aluminum piano, but just didn’t work. And what happened was Steinway tried to set fire to one of his pianos for Mr. Gibbs to show him that it would not burn. Finally, he relented to have a wooden piano or two on the ship and a wooden butcher’s block. That was it. Well, Gibbs had watched the Normandie catch on fire in New York Harbour and capsize right there at the dock. They had asked him to rebuild her, and he said, “No, I can’t do that” and they eventually scrapped her. But if you look at the video of the Normandie on fire and sinking, it’s something to remember.

ALEX: So, we’ll switch now to discuss Turn It Up! your documentary about the world’s love affair with the electric guitar. Are you a musician yourself or just a fan of that particular instrument?

I played in bands for about seven years from junior high until college. When I went to become a filmmaker, I retired my 68 Gibson to under my bed where it’s been appreciating ever since, but yes, I was a musician and I can still fake it, but I know real musicians, and my biggest fear was that one of these guys like Slash would hand me the guitar and say, ‘Hey, let’s jam’, you know? I directed the ‘Tender Is The Night’ video for Jackson Browne, and I have a recurring dream that I’m on stage as his lead guitar player and we’re in a concert and Jackson’s singing and he turns to me to do the solo, and I can’t remember it at all. Even with some of the musicians that have become really good friends from this experience, I’m reticent to jam with them because I am so out of practice. But I have six guitars and that’s a very modest little collection, and I’m not worthy of any of them.

ALEX: In addition to Slash from Guns & Roses, you spoke to many other musical legends. Did you have any favourites that really stuck out?

Yes. Let’s see. I came to Los Angeles to do The Doors film in 1981. This was 10 years before Oliver Stone successfully put it together. I had actually started filming with The Doors in 81 and 82 at Père Lachaise in Paris, where Jim Morrison is buried and Robby. Krieger became a very good friend. He was one of the very first musicians to sign on. I think he felt kind of bad because it didn’t end really well (my The Doors film). I had raised $3 million to do that film, and then Ray Manzarek wanted to go on and do the big Hollywood version suddenly, with John Travolta playing Jim Morrison. I tried to explain to them that that was not a good idea…

B.B. King in particular left my whole crew buzzing for like two weeks. It was very hard to get with him and finally, we were able to catch up with him at the one of the Native American casinos out here it was the Chumash Casino, just north of Santa Barbara. He was in the back of his bus with the diesel rumbling underneath him and his little state room there. We were told many times over that we would get 20 minutes and not one second more with the man and that we would be forcibly ejected after that – his handlers were not nice, but he was and I had done my homework. I had read his autobiography and an off colour story that he wrote, stuck with me and this is how I started the interview with him.

By the way, I think prep is the most important thing a director can do, and this is a good example of it.

BB King wrote that his mother was wooed by a suitor named Mr. Wright, and everybody did not like Mr. Wright because he would constantly kick their cat. They liked the cat – They didn’t like Mr. Wright, and he was there all the time wooing the mom. So, BB just decided that he would play a trick on Mr. Wright, and he tied one end of thin fishing line to the cat and the other end to Mr. Wright’s testicles. Now it’s like, what? How do you do that? So, I’m reading this, and when Mr. Wright finally kicks the cat, he gets the surprise of his life! Yeah. So, we’re seated down in his little room on the bus, my wife is there, Doug Forbes, who was one of the producers, and the cameraman. So, I say, “Mr. King, there’s something I really need to know. I read your autobiography and I don’t understand it.”

And he goes, “Yes. What is it? Maybe I can help.”

I said, “How did you tie the line to Mr. Wright’s testicles?”

He looks at me and he starts smiling. He grins, and then he starts to laugh, and then he starts to belly laugh and hold his stomach. He was a very big man at this point and then he falls over to the left, just laughing. And I had him at that point. He gave us an hour and a half right there. His band was vamping on stage and the handlers kept coming in and saying, “Mr. King, you’re on.” and he would whisk them away, “Go away, leave me alone.” He was having too much fun. When you interview a guy like that you usually get the standard old stuff, but I got deeper with him.

One of the things about Turn It Up is in the original packaging. There was a second disc, which is my extended conversations with the artists. I went to find little blurbs for the internet in the outtakes, and I start watching the interviews and it was like, Jesus, if I don’t do that, nobody will see this really intensive interview with B.B. or Slash or Skunk Baxter or Robby Krieger. So, all by myself on my Mac, I mastered that second disc, and I think it’s as interesting as the film, but not as polished, of course.

But back to Mr. Wright. B.B. said that Mr. Wright was a sharecropper and had worn out jeans and he was sitting on a cane chair, which didn’t have all its rungs and as such, his ‘bits’ were hanging down there. I don’t know if this is true or not, but that was his story. He’s got a gentle touch that B.B. King…

ALEX: It sounds like it! How did Kevin Bacon get involved with the film? Was he one of the first to sign on or did you get him after you had all the rest signed on?

Pretty much the latter. Richard Arlook, the same guy who became our executive producer, he had been the head of literary at the Gersh Agency, which is a boutique agency in Beverly Hills. They’ve had some very, very famous people over the years and Kyra Sedgwick (Kevin Bacon’s wife), was one of their clients. So, he called Kyra and said, ‘Do you think Kevin would be interested in being our host and narrator?’

30 minutes later, I get a call saying, ‘Yeah, he said, Yes, let’s make a plan.’ He was great. I sent him home a little early and he was very pleased about that. But, you know, he was credible and he knew his stuff so it was very easy to work with him.

What I didn’t say about B.B. King is after spending that hour and a half with him, my crew and I felt like we had met really a great person. I think when you meet famous people, great people, whatever the discipline is, they have the same kind of command of themselves and discipline itself. You felt that with B.B. and he let his guard down with me and man, for days, people on the crew were saying, “that was so inspiring” and it really was and like an idiot I left my guitar home because it’s just like his Lucille, and I wanted him to sign it. But I was afraid with 20 minutes that would get in the way, right? But I did get to show him a picture of me and my band, the late W. Moulton, and there I am, standing in 1968 with my guitar that was just like his. He looked at that picture and says, “May I keep this?” I said, “Yes, of course; I named mine Maybelle. Because you named yours Lucille.” I gave him the photo and it was very sweet.

ALEX: You mentioned that you’re working right now with Adam Carolla and Nate Adams for Chassy Media’s ‘Cars, Guitars and Other Obsessions’ series What can you tell us about that?

Nate Adams’ consistently made some of the best automotive films I’ve ever seen. In fact, I think their Shelby American documentary has more impact than the Ferrari versus Ford feature film.

ALEX: Really?

Yeah, I really do. Because it’s the real Shelby people. It’s Carol himself. It’s his family, it’s the Fords, and they really did their homework. They got incredible access and because I thought in the feature film that Shelby was treated pretty much like a two-dimensional character and not the really interesting person that he was.

So, I approached them with two ideas. One was ‘Cars and Guitars’, which has now morphed into ‘Cars, Guitars and other Obsessions’, to make the possibilities even wider because people have other interests and so it’s not too limited, and the other is ‘Speed Geeks: The Science of Speed’ and with that I brought a guy named Steve Huff, who’s a racer of motorcycles, cars, hydrofoils, and dragsters He holds the electric dragster record. He went over 200 MPH in an electric dragster in the quarter mile and he’s just a very interesting dude, who is really into the science of what he does. We’re basically doing a series about what makes things go fast and not just how fast they went, but how you were able to achieve that speed so there can be an electric dragster, a bullet train, Apollo Ono or the SS United States. Anything that makes speed can be an episode.

To me, it is like a combination of Live at Daryl’s House, Daryl Hall’s performance show where musicians come and visit him and something like Top Gear. You know, on Daryl Hall’s show, when they’re done playing music, they go and have dinner. In my show, they’d go for a ride in whatever spectacular car we’re talking about. It’s evolved from there, because now we know some guitar players who also collect stamps and one guy who is the biggest comic book collection in the world and stuff like that, you know, Seymour Duncan, who’s the featured in Turn It Up! is the guitar pickup guru. Well he has an Indian arrowhead collection, and that is his main passion. So, he’s either wandering the deserts looking for them, or he’s making them himself. So, the stories go on and on and on. All of these rock stars and other celebrities are just regular people who have massive passions for things. When I did Turn It Up!, I made a lot of friends in the music business and I befriended a lot of the managers. So, it makes it a lot easier to get to these people now.

EOIN: The Best of the Best was your motion picture directorial debut. How did you become attached to the project?

I’ve never told anybody the truth before. Most of the good things that have happened in my career have come through my wife, Kitty. I met her in The Doors manager’s office on the day my Doors film fell through. She and a blonde walked in and my day got a lot brighter and I knew I was going to marry her (laughs). Just right there, nothing like that had ever happened to me before.

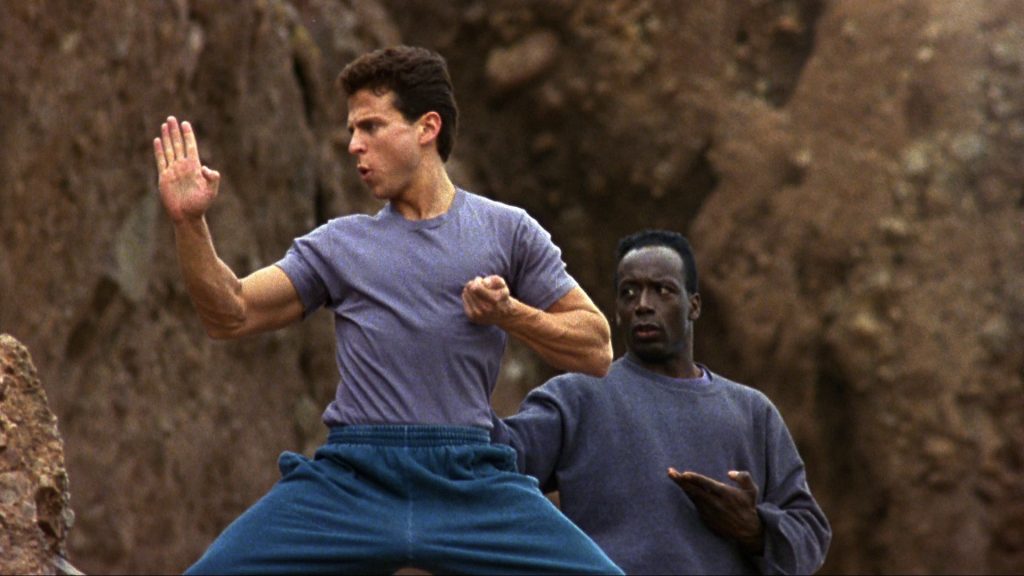

What happened was she saw an ad, I think it was in The Hollywood Reporter and it was for a director, for a martial arts film. I knew a lot about boxing. My dad was a boxer and I watched boxing for my whole childhood. Somehow Philip Rhee called me back; he liked what I wrote, and when he looked at my music videos, which were happening right then.

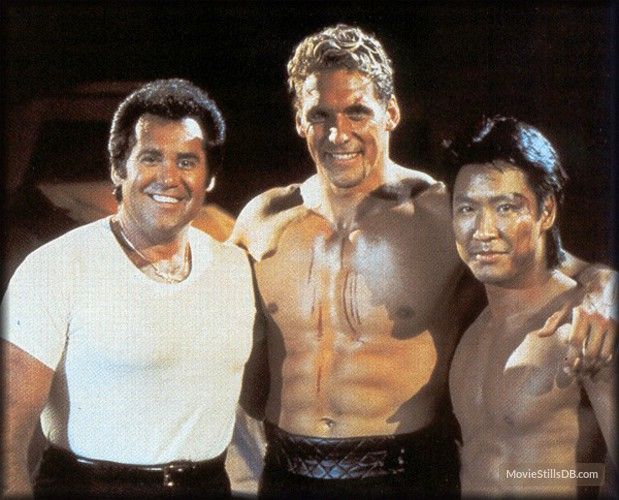

When the Doors film fell apart, I had met Bill Siddons, The Doors Manager, and he was now Crosby Stills and Nash’s manager. That’s how I got my first music video from Crosby Stills and Nash – Southern Cross. Philip saw my Survivor video that really turned the tide for me. He saw in that video (“I Can’t Hold Back” was the name of the tune) the use of non-verbal communication, the eyes telling the story as opposed to the mouth. That is what he wanted in Best of the Best so we met and we became friends. I convinced him that we’d have fun working together, and I was very, very impressed with him as a martial artist and as a person. He is a lovely, disciplined guy who’s not afraid to laugh. His brother Simon who played Dae Han Park the bad guy in the first one, is the nicest man in the world and took the brunt of a lot of punishment. For instance, Simon is seen in the waterfall, I think, in Best of the Best 1 in Korea, and that really was a waterfall in Korea, and it really was 33 degrees in the water. Simon came out of that crying and I was freezing and I wasn’t in the waterfall, and he would always get the brunt of the pugil sticks whenever we were practicing a move. Simon would always get it in the nuts, and it was like a constant thing (laughing). Simon took the pain for the entire production. But between him and Philip, it was just a pleasure to work with those guys on my first feature. Peter Strauss, also who was the executive producer, I didn’t know how good I had it in my first film and what great people I was working with.

EOIN: It’s actually one of the few martial arts movies where I tear up at the end every time I watch it…

I tear up too but not for the same reason (laughs). I must say Best of the Best 2 is my favourite because I got to get my own chops and there’s a dark sense of humour in the second one. That’s me as manifested through Wayne Newton. But the first one, I think I kind of let Eric Roberts get a little too teary at times, but I’m thrilled to hear that it worked on you because I went to see it in a movie theatre when Best 1 first came out. As I walked out of there, I talked to one of the ushers who had seen it 60 times and I said, “Good movie, huh?” and he goes, “Yeah, but it’s a little too teary for me (laughs)”. From that moment on, I thought, Gee, I let Eric kind of chew some of the scenes that I probably shouldn’t have. But as a first-time director you can be a little intimidated by an actor like him. He truly lives the part he’s playing, and it can get kind of intense. Eric’s a very intense guy.

EOIN: I get that. He comes across like he would be intense.

Yeah, I mean, probably much more intense back then. I hold the world record for directing Eric Roberts at 3 in that I did another film called TNT and he was in it as kind of a tech geek CEO. Frankly, we had a blast working on that one, but that was just for a few days. When we did Best of the Best 2 it was difficult for everybody because we shot a lot of it out in Mojave and around Mojave, in the desert and the train goes by there at night, every half hour. I mean a freight train with a whistle, you know? And I think the crew did not sleep for two weeks. So it got a little intense for everybody because of that.

EOIN: I could imagine. I have a question from Duvien Ho who says the drama and the martial arts flow seamlessly. Were there any challenges melding the emotional with the physical?

Hmm. You know, I think almost everybody who played in these movies realised that wasn’t just another chop-socky movie, and they wanted to do something of quality. I must say Philip and I, Philip being the fight choreographer along with Simon in the first one anyway. It made that part easy. See, I was an editor before I was ever a director, and I think it’s the best training for filmmaking because you know what shots you need and you can see the scene and you know how much of the scene you got and you know when it’s time to move on. Which is why I did a lot of episodic TV. I could make my days because of that.

Anyway, I think between Philip and really trying to up his game to work beside Eric and the wonderful choreography that he and Simon brought to it, it was easy for me with my editor’s brain on to find the right angles. I’m very pleased with those movies because it really looks like people are getting hit. As a matter of fact, in the final fight scene with Philip and Simon fighting each other, Philip really did get kicked and I think Simon did, too. They actually kicked each other in the head. So when you see that sweat go flying off, that’s what happens when you get kicked in the face. But that was on purpose. And the other thing is I always wanted closer and closer coverage, so it felt like you were getting into the fight. And it was harder back then because cameras were big. There were no Osmos and iPhones. But Jerry Watson and he became the camera operator and became the DP on number two when Fred Tammes got sick. He was great at getting into the action and in fact, I think in both films he got black eyes from getting kicked in the camera (laughs) and I felt bad, but we got great shots and he was willing to take those risks.

EOIN: You directed Parts 1 & 2. Were you ever interested in pursuing any other sequels or had any story ideas?

No, I think after two, I went off and did a lot of other things, and I think Philip really wanted to be a director. He had been on films before Best of the Best. He had done some very low budget martial arts films that were fairly high quality, especially the martial arts parts. I think he really wanted to direct, and he had the trust of Mr. Strauss, the money guy so they did it without me, but mine made more money (laughs). I think if there’s ever a reboot and I hope there will be, I hope that Philip and I work together again because I think I have a better handle on the dramatic side. He has the best handle I’ve ever seen on the on the martial arts side and the choreography side, and he has some great new ideas.

He told me that a lot of people believe that Best of the Best 2 was the origin of mixed martial arts. If you think about it, that did not exist before that movie, as far as I know. We had wrestlers against boxers and Tae Kwon Do guys against muscle men and all the different disciplines in the final fights and in Best 2. So maybe it’s really true that that’s where mixed martial arts got started. I look at it now, I looked at it last night and I was like “shit! That looks like mixed martial arts to me (laughs).”

EOIN: Kane Hodder makes an appearance as different characters in the movies. Is he a friend of yours or someone else from the movie?

He was a friend of Simon’s I believe and probably Phillips as well is just, you know, at that point, he hadn’t found fame and wasn’t Jason Voorhees yet. He was just a great stuntman and the guy is just hysterical so it’s great to have him on the set, and he has no fear. So, no, he came through the Rhees.

One other point that I might make is we were the first people to film the Korean Black Berets, as far as I know. That was really interesting and they all were smokers. That was the funniest thing between takes they’d all smoke (laughs). These incredible physical specimens. There was a point there where we were in Korea, we were at the Black Berets’ Secret Camp and a guy with a machine gun a Korean soldier came in to inspect the bus for contraband. My heart sunk because I knew that one of the crew members had some stuff in a particular piece of equipment that I would still be there. So that was the scariest point for me on Best of the Best 1. It’s just kind of an aside, but nobody expected that but yeah, I still could be there; my son had just been born and then, no, that would not have been good.

ALEX: So let me ask you about the first Best of the Best because I watched it recently as well. One thing I really noticed about the movie, which I don’t know if I noticed the first time or not, it was just one of those subliminal things when they’re having the final fight in the arena. You really work with lights and darks. You establish the fact that the arena’s massive even though we don’t see all the audience and it makes it very tight and you get kind of drawn into the action just because of the way the darks work. You’re only concentrating on the stage. Was that intentional or is that budgetary as well?

I think both. When you’re doing something like this, they tell me how many days you can afford to be in that building and to be with that crew and how many days you can have extras. I think it was only one day that we had a massive amount of extras. We actually went to Korean church groups and they brought in lots and lots of Asian folk to simulate shooting in Korea. We used those days for credibility. The opening scene, the first fights, there were a lot of people there. But as we got into the coverage, like in those final fights, I don’t think we could afford it. We did have a certain amount of people that we could move around the auditorium but we were working on longer lenses and things, and you really didn’t see them, except kind of like an out of focus presence, I think.

So yeah, later, as we got into the nitty gritty of the fighting, we had many fewer people there and that’s really the practical thing. But I saw at one point what it looked like with just one spotlight on them, and it was the most dramatic single shot that we had. So I decided with Doug Ryan, who had become the DP, that the very final fights in the very final moves should be just that one spotlight; that’s the beauty of filmmaking. You can put people’s eyes right where you want, and there’s no better way than one light – a spotlight so that was very intentional. I’m glad you noticed that because, yeah, I think the drama part worked. And by the way, I’m glad you cried at the end of it. I I’m just a little insecure. That’s all.

EOIN: I cry a lot.

ALEX: He does cry a lot. After this, you went and did a bunch of other things, but then you returned again to the martial arts world with Showdown. What did you bring, if anything, to Showdown from your experience with Best of the Best?

I brought Patrick Kilpatrick as the bad guy. He was one of the guys in Best 2 that attacked the little Indian place and he is one edgy dude. So I kind of loved him because he used to be an advertising copywriter. So every day he’d come to the set with the scene completely rewritten and I’d listen because good directors do listen. Sometimes he had some good stuff, but sometimes actually it was so over the top. But I still respected him for that, and I wanted edgy as we moved into Showdown. So I brought him. But I think Jeff Imada, if I’m not mistaken, was the stunt choreographer and so not that much, except my own knowledge. But it was a lot smaller budget. And by the way Best 2 was the only time in my entire career that I have been comfortable with the budget. Some of the other stuff I did, like Substitute 3 and 4, were like 14 days of shooting and I never want to do that again. It’s just not enough time to do it right and I had been doing so much episodic work that I was able to pull it off, but it was very hard. I wish I had fought harder for more days, but that was what it was. I didn’t make those deals, you know?

ALEX: Yeah, that that does make for a pretty tight shoot, although that’s not totally unheard of, even nowadays.

Nowadays it’s a little different because you need a fraction as much light. For instance, a lot of my stuff was shot in Vegas like Jackson Brown’s Tender is the Night and the fantasy scenes in Best of the Best 2. Part of the reason I did that was because it’s lit. All I needed was some film light. But back then, the camera and the film were really slow. So it wasn’t so easy to do something in 14 days. The lighting took time and we tried to do it right and you also couldn’t see that well, but I guess I could in a video monitor what I was getting. But it was harder to visualise what was going to be on the film back then than it is now in the actual video. So yes, it is possible to do it. I think these days the budgets are either $200000 or $200 million. There’s not much in the middle. I think the kinds of films I was making for $3 to $8 million are more rare these days.

EOIN: They definitely are. There were movies from the 80s and 90s where the budget was like $5 to $10 million even. And you rarely see that these days.

Right? And not only that, but most of the money went to the actors as it did in The Best of the Best and also the Substitute movies; Treat Williams probably made half the budget.

EOIN: John Jerva asks what do you think is the enduring appeal of these movies? Some of them are nearly 30 years old and we’re still talking about them, why do you think that is?

I think on Best of the Best 1 in particular, it explains the mindset of the martial artist. It talks about discipline and also about restraint. In these movies, the martial artists, the black belts are not aggressors. They’re the guys who save the day and only fight when they have to. I think that’s the universal lesson. I think one of the reasons we’re still talking about these films is that a lot of karate dojos played these films for their students to show them the correct mindset of a martial artist. Best of the Best 2? I don’t know, I guess there’s a certain amount of that, but that one was just a whole lot more fun. Wayne Newton and I early on said “let’s just walk this really thin line between good and bad taste for your character” and that was easy for him so I had a blast working with him.

Anyway, the first time I saw him we had rented this mansion to do Brakus’ lair and Wayne was in the refrigerator. I walked into a room and they said, “Mr. Newton has just shown up and he’s in the kitchen. Go say hi”. I walk in and I see a guy in a tuxedo but his entire front of his body is in a refrigerator, his head is in the freezer and the rest of him is in the refrigerator and he turns. He goes, “Oh just cooling off, are you Bob? (laughs)”. Just a surreal intro. Subsequently, we became friends. He invited my wife and I down to his home in Vegas, where he has a zoo and is right on the on the airport tarmac almost. It’s right behind McCarran airport. His prized stallion that he showed me bit me and took a giant chunk out of my leather jacket. Thank God I was wearing one. It just held me there looking at me with his angry eye. I realized if I punched that horse that Wayne would probably kill me because it was worth much more than I was (laughs). Later that same day after I got my jacket free and it still has a big hole in it, we were looking at his penguin compound; he has a zookeeper there, and she was showing my wife and I and some other people the warm weather penguins that Wayne has and everybody is petting it. As she puts it in front of me, she says “be careful. It has razor sharp claws”. Maybe it was the beak but at that moment it also bit me.

ALEX: That was not your day…

I bled too so we bleed for our art (laughs), but I enjoyed working with Wayne and he was a real trooper. He was flying his own Gulfstream, I think, or King Air from Vegas to downtown L.A. or some airport and then helicoptering over. He was flying his own aircraft and even when he had the flu, he never stopped smiling and working hard. So I can’t say enough about him and when you ask for sleazy, it was there.

ALEX: He seemed to relish that role. Obviously, he’s not an evil club runner (that we know of) apart from the evil zoo, but he seemed to really, really like that over-the-top personality…

Yeah, because if you’re fighting for the death, I mean, I think we could all see Wayne Newton as the underground person running the thing. That’s why his name came up in the first place and because it was just natural. But I think he relishes it because we were having so much fun.

I pride myself on being kind of a good guy director, and I want to talk to that too. Regarding Sonny Landham on a scene in Best 2.

So I make it easy, and I make it as funny as possible and as fun as possible, so we just had a blast working together testing the limits of bad taste, you know? That just came so natural to him and when it was his last day on the set, we were all really sad. It was really incredible.

I have yelled once in my filmmaking career and on purpose; it was a pivotal scene in Best of the Best 2 where Sonny Landham does this kind of death run where he’s trying to save his mom and the kid and all the good guys. Right before it was time to shoot that and he was going to have to take about 11 Squib hits. He chickened out for lack of a better word. He was such a big, burly, guy, a man’s man that it was hard to wrap my head around the fact that he was afraid. I think he got himself deeper and deeper into kind of a paranoia about it where he didn’t want to be hurt. I guess he had been hurt by squibs before and this was like a lot of them. So, he starts telling me how he was going to what he would do and what he wouldn’t do. OK. And I said, Yeah, you can do that, but that’s not what’s in the script. You either have to do it the way it’s written or I have to write this scene out. I don’t know how we write out a pivotal scene like this, but I will if I have to.

We kind of had a few little mini meetings on the set and I finally saw I wasn’t getting anywhere, and he was getting more and more perturbed. So, I told my assistant director, I’m about to throw my coffee cup right near him and scream, “|I’ll meet you behind the building in five minutes” to my assistant director. So, I did I. I yelled, I said “fine, fuck all this. This scene is out of the movie. Go home, Sonny”. Of course, that did it.

So, I waited behind the building that we were filming in, and after a while they came out and got me and said “No, he’s willing to do it now” and he did it. They don’t tell you in film school how much is psychological, what your job is, how you have to get your day, no matter how bad it is and that’s how I got that one. It was the one time I yelled, Yeah. But it worked.

ALEX: You’ve done movies and television and video. Is there any one genre or medium that you feel more comfortable with or you’re happy to do them all?

My biggest pleasure and maybe my biggest downfall was the fact that I was kind of a jack of all trades that, yes, I became more famous for action movies, but I was originally a documentarian and really, the thing I really wanted to do was surrealism. Had I done The Doors movie that I wanted to make where it would have been Morrison talking you through his visions from the grave. That’s the movie I really wanted to make because I was a fan of Luis Bunuel and Fellini; I thought I could bring those kinds of really surrealistic sensitivities to Jim Morrison’s story. What I was going to do for The Doors film was going to be never having an actor play Morrison and only seeing his visions and using the footage that existed of him in his own films that he made at UCLA and also in the films that Frank Lisciandro, his good drinking buddy and filmmaker made for a year following The Doors around at their peak, there was a lot of footage of The Doors all over the place.

As an editor, when I heard The Doors American Prayer album, which was Jim’s poetry put to music ten years after his death, I saw the movie in my head and I sold all The Doors on that I understood what it should look and feel like. It should be a seance, not what Oliver Stone did. Of course, when Oliver Stone did his shtick, The Doors immediately kind of turned on it because it really wasn’t the way it was at a Doors concert. People didn’t dance. They watched, there was danger.

So to do the film I wanted to do, I needed The Doors poetry and to get The Doors poetry I had to make friends with Corky Courson, who was Jim’s wife’s dad, he was a bomber pilot in World War Two and the boss of the Disneyland Hotel. Very straight, man, but a very good man. I met with him. He finally trusted me after, like a year of trying to use the poetry of Morrison, which he controlled in the film I wanted to make. But there were certain stipulations. There were certain scenes that involved his daughter that The Doors could not portray and it really wasn’t much, but it was enough that The Doors and particularly Ray Manzarek, said “No, we’re not going to be dictated to by the estate”. That’s why my film fell apart right after I’d gotten the estate on board, which is really sad because we were almost there. But it would have been a very different kind of documentary that never would have felt like a documentary. That’s what I really wanted to do. But the next thing I’m going to do is a video blog about my stories, and it’s going to be called Big Bassou’s Bedtime Stories, and I’m going to tell all the stories I’m not telling you. Well, there’s some off colour ones, and there’s some behind the scenes stuff that could be a lot of fun, but I realize I have so many stories. I have six pages of them in an outline, that I’m just going to start making these little films about my stories and maybe illustrate them with footage from my work. My son is a computer geek and he’s a senior coder for Lyft and is so state of the art and his wife too Karen, they are really encouraging me to do this, and they’re visiting in two weeks and we’re going to start. I mean, I would have a different shirt for every one.

ALEX: But no pants?

No, why would I need pants? (laughs)