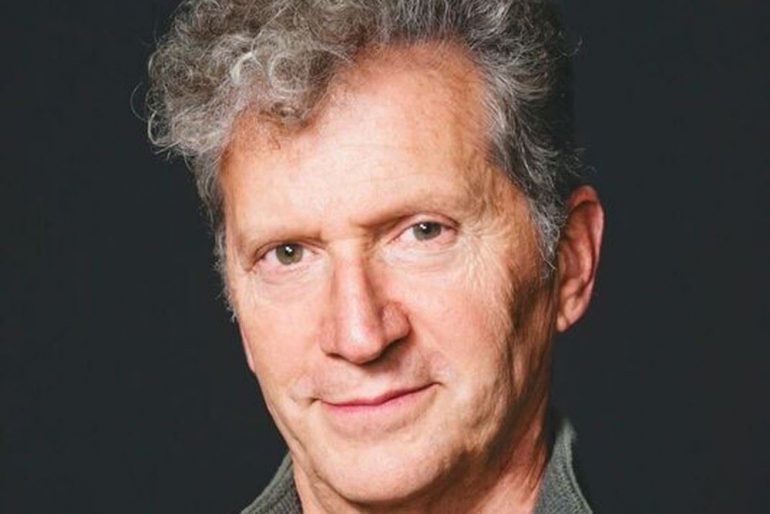

Brad Fiedel composed the music to Fright Night, True Lies, Striking Distance, The Terminator, Terminator 2: Judgment Day and many more. He was kind enough to chat with us about his career as a film composer and what he has been working on recently.

The opening credits theme to Terminator 2 remains arguably the greatest opening music to a film ever. How did you go about creating such an iconic sound?

It was interesting because it really was one of the key scenes as I looked at it; now some of it of course was CG which wasn’t even completed when I was composing the music. In the old days it would just be a black screen and it would say “scene missing” (laughs) but I knew the script and I knew the content. What it really did was it caused me to really start shifting my ideas. This was very rare for a composer as I got to read the script before you’re hired or get started. Of course, as this was a sequel James Cameron had given me the script early on. Then he started to ship me little pieces from the editing room so I could see what the look was; so the content of the scene had a lot of pathos I would say. It really told me that needed to shift the texture and the quality of the orchestration of the theme: Number 1 – just the depth and the sound need to have more warmth in it as opposed to the original Terminator which is just dark and blue and very edgy. Then also, my God you’re also seeing the destruction of humanity and it caused me to add a new section to the theme where there is a choral type sound. There were some choir type sounds in the background in the original Terminator especially in that underground future sequence where you saw people suffering. This was just a bigger, expanded, warmer sound and I was using a whole new technology. I had these two Australian Fairlight computers and they were way closer if I wanted something that sounded like a large group of human voices I could get a lot closer with that technology.

Having worked with James Cameron on 3 pictures, how involved is he with the scoring process for his movies? Did he sit with you and go over it closely?

No, he doesn’t have the time for that. So, he is very closely involved with every single thing that is in every single frame of his films. I mean, I really do believe that; I don’t mean this as an insult. You know, if he could score the films himself, he probably would and I get that because I’m a control freak in my own area as well. But he has to take that leap of faith, whether it was me or James Horner and one other composer he worked with was Alan Silvestri on The Abyss. He did three films with me and 3 or 4 with James Horner; there’s a leap that has to happen. The other thing is his literal time availability so there’s no way he could be over my shoulder in the composing. Thank God! I can’t think of a composer that would want a director present in the creating part. It’s the Show & Tell. I sit alone in my studio and create things so when I have enough to show him and I thought it was worthy of him for a visit I would let his office know and they would say “he’s shooting; he’ll be there at 10 o’clock tonight”. Pretty often I might be sitting there at 1 in the morning still waiting for him to come because that’s filmmaking. He would come in and it would need to be very efficient – “Jim, here’s this!” and he’d say “great, but please focus a little more this way” or I would say “here’s what I’m thinking for the T-1000” and he’d say “Woah, that’s too avant-garde for me!” but there were a few things I had to talk him into on T2.

One was this weird cacophonous sound, sometimes dissonant a-tonal sound I would use for some of the fighting with the T-1000. The way I convinced him was by saying “Jim, you’re creating visuals that no one has ever seen before or anything like this; if I do this with typical scoring it’s not going to do them justice”. So that was one of the rare times where he actually listened again and said “okay”.

My brother Greg has been wanting me to ask you what the time signature is for the main theme to Terminator?

It really doesn’t exist, you know. I mean, I think I forgot. I think they came up with so many people have looked at that. They came up with 13/8 or something like that. It was a mistake, basically. There wasn’t MIDI, the musical instrument, digital interface was not available on the instruments yet that I was working with. It had started to be around, but it just wasn’t quite ready for me to jump into in the pressure of time of composing a score. So there were there was this Prophet 10 and it had like its own little built in digital sequencer where you could play something and it would play it back and it wouldn’t play it back analog. It would literally like a play or piano would play it back. Right. But it was this little teeny part of the keyboard. And you had to push record, I think, or start and stop. So I wanted to make a loop of that *mimics Terminator theme* sound. And I guess when I when I pushed stop, it wasn’t completely six. I was hearing it kind of in six, eight, which is more like what Terminator 2 is. And it’s just a little shy of that. And it was like there was something about it that I thought kept you propelling forward. I thought that’s part of creativity is recognizing the value of some of your mistakes and incorporating them. I think that’s a big part at times for all creative people, is not to reject things just cause they’re not what you expected. So I listen to it and I said, “I like this”. It’s kind of falling forward. It’s not like an easy time. So it worked for me, so I just played everything against the seat of the pants and just like you’re working with a drummer and he’s doing something weird, but you just got to play your melody and work on top of it, you know?

You’ve worked in television on shows like Timecop and films providing scores; did you have preference? Does film allow you more time to be creative?

Wow. It’s quite different, and I’m not sure now, because this was a while ago that I was doing these television projects; Timecop was one of the very few things I ever did that was kind of had to relate to something that I didn’t originally compose. Anyway, So Midnight Caller, Reasonable Doubts, things that I really created the template for. In many cases, I did not have the time to do every episode. At that point in my career, so I had Bob Singer, who produced a number of TV things that I worked on and. What I did often was I would do the pilot the first episode and really set the score. What is the sound of it? What’s the instrumentation? What’s the melody? And then I had my dear friend, Ross Levinson, who I trusted musically with my life, in a sense. He played electric violin on a lot of my scores, he was very talented as a composer as well. So we had this great partnership and I got Bob to trust the situation where we would talk through an episode. He would go off and compose it, show it to me. And by the end, he wasn’t even showing me stuff because we just would have the shorthand. And I was kind of supervising composer as opposed to the actual in the trenches composer on many of the episodes. Never did that in a film. Even though film started especially big summer releases, the schedules would get more and more crunched as politically the studio would wait to the last minute to greenlight the picture and then everything would get slow. But it had to be done on July Fourth for the release. Right. The series schedule was kind of like clockwork; there was a rhythm to it. Shooting, editing, post-production. Shoot it. You know how all the episodes are working. Film was more pressured, though TV you have to be fast. But you know your material, you know, after the pilot, you kind of know where you are. You know the language that you’re using. But for films, I really tried to come up with a new language for every score in a sense. That was the fun part creatively for me and I think that’s where I did my best work, where I come up with something a little different but memorable for the score. So it was really that had to happen and sometimes 24 to 48 hours, the original like getting approval, like Jim Cameron showed me Terminator, I believe by the next afternoon I showed him the main title (laughs).

I always loved your score to Striking Distance but I don’t think it was ever fully released, was it?

You know, I’m in discussion right now on a number of scores that were never released. Main reason first of all is the film didn’t really take off like they’d hoped. And thank you. I enjoyed that score and frankly, I think it’s why I ended up doing True Lies, because Jim knew me as an electronic composer. He didn’t really know me well, even though I’d done a lot of orchestra work since the early 80s. He didn’t really know that part of me. He screened Striking Distance and I think that helped him kind of realize I knew how to handle an orchestra. Not that Striking Distance and True Lies are similar but they are similar in the fact that it was a big orchestra combined with what I did in my studio back in the day, because I did everything through the musicians union. Releasing a soundtrack on a film that had full orchestra was very expensive. The reuse payments that had to be made. Deservedly so, I think to the musicians. I have nothing against it but it kind of made the business plan for releasing certain scores not make sense. True Lies was a big enough deal that made sense. But there are a number of scores I did that at least had a big string section or an orchestra that never were released. The union kind of saw the reality that a lot of these scores wouldn’t be released and that there was a core group of very devoted film score fans out there, and they made a special new rule that if you if you pressed 5000 or less. I’m saying press. You know, the old vinyl days (laughs). But, you know, if you released. Well, now we’re back. But anyway, he released 5000 or less. They made it very affordable. So there are some record people now that are kind of exploring with me, number one. What do I have that wasn’t released? Striking Distance being one of them. And what do I actually have the material from? Because some of them go so far back that it was old analog tapes that have since just deteriorated. I did finally have enough thought pretty much in the 90s to start doing the scores and storing them on DATs. So then recently I got some of those transfer just to wav files. So I do have some stuff available. I would love to see Fright Night; I made my own little release just for the people involved and friends. It was a cassette (laughs). Oh man. I’m dating myself. But yeah. So maybe there’s hope for that…

Hopefully, yeah. I mean there are companies like La La Land Records who are bringing a lot of scores out that were never released properly.

My score for The Accused I believe was recently released which had a string section in it with like 40 musicians. I can’t tell you even which label did it but things are happening.

Any plans to return to your one man show Borrowed Time? I’ve seen parts of it on YouTube..

(laughs) Oh, man. Did I hang myself out to dry on that one; it was like so personal. I hadn’t been performing live for so many years. I was just looking at the video because somebody asked me a question, I went back and looked at the video of a particular song from that. It was autobiographical. It was 90 minutes long with no intermission. I mean, it was a marathon – Dialog. I played other characters, in a sense, when I was having interactions. It was just me onstage with a piano and my foolish self and wow. It was really nerve wracking. And it was really satisfying. And I really did feel, you know, when I look back at some of the stuff I did, I’m like, oh, my God. I totally exposed myself. I actually took a workshop and the whole thing about one person shows is the whole idea is to dig deeper and deeper to your authentic self and don’t worry about what’s ugly and just share it. And I’m not sure I would ever want to go back there, number one. Number two, man, it really required a lot of memorization. I had to remember every chord, every lyric, every piece of dialog. It was all written. It wasn’t like an ad lib. I was up there just screwing around every single word and every note in that I was preordained for what I needed to do. But, you know, I never say never; could be that that, especially in the UK, I’m seeing a lot of interest. You guys are really. You are in the U.K., right?

I’m from the U.K. initially, but we actually live in Canada.

Ah ok. Anyway, outside the US there, I’ve always known this, but social media makes it clear that the level of fandom level of caring about stuff, even from some of my stuff, obviously is so, so many years ago, you know, so that I’m thinking because I go to London all the time as my daughter’s living there. I was thinking that I might do some appearances there and it’s a small theater or whatever and maybe do some kind of Q and A, but also maybe some parts of Borrowed Time.

Following up on the performance of Borrowed Time, your brand-new project is musical theater, entitle Full Circle. What can you tell us about that and how it came about?

It’s mostly about this teenage girl who’s stuck in an apartment in New York who has no filters, she’s almost like what might be called in sci fi, an empath. When her grandfather has a stroke and can’t speak, she actually hears his thoughts as singing. He kind of sings to her from his brain because that part of his brain works, the speaking part does not. It came about because I had had a few story ideas that I wanted to try to bring to life and one of them is the idea that we all walked through the world. I lived in New York a lot and I literally, to get to an appointment sometimes had to step over a homeless, out of it person on the sidewalk. I didn’t stop and say, “what’s up, man? What can I do for you? You OK?” You know? So that whole idea of how we close our empathy off to survive in the modern world especially, intrigued me. So, I created this character, this young girl who literally can’t leave her apartment anymore because it’s heightened and heightened to the point where it’s just too painful for her to go outside and she can’t even control it. She’s kind of almost goes into a seizure from everything that’s coming at her, all the stimulation. So that was really the main driving force. And then I had this whole separate idea that about her grandfather, who is estranged, coming into the picture.

Creativity is kind of mysterious to me. I don’t like to take it apart too much but when I look back at all, how did I come up with all that? I mean, it’s a whole two act full musical; I wrote the script and I wrote the lyrics and the music; which is a lot so don’t try that at home! (laughs). But it’s one of the reasons it took me so long because I’d have to walk away to get any objectivity. I didn’t have a partner or somebody saying, “yeah dude… no”. So, I had to like fumble through it and do different versions. But I’ve always loved live theater and (unlike Borrowed Time), this one is not me, and I got to work with some wonderful cast members and just something I wanted to take on.

You mentioned creativity to a huge role. Do you find it tougher or easier to write for a project when presented with a rough theme/look or prefer going at with a blank slate?

The blank slate is a really important part of it, but not quite the way you’re saying it. Most of the time a composer is hired. The film has already been shot and there’s at least a rough cut. OK, so the film is there. You can just see it, you know, occasionally, like in T2. I had this script before the shoot, but most of the time they don’t decide who is going to compose the music until they’re kind of coming down into the post-production territory. So, my big thing was to get them to show me the film with no temp music, temp music, which has gotten easier and easier to get very, very elaborate with. In the old days, it was kind of hard because people were on Moviolas and there weren’t that many tracks available to run extra music tracks, it could only run it during quiet moments when they didn’t have dialog or whatever. But now, because of digital editing, they can do this fully blown score and it’s got every best cue from every movie you can imagine because they’re trying to make sure the studio or the powers that be, like the movie and get behind it. So, it’s partially a sales tool, it’s partially a tool for the director to see how the scenes are working. But for a composer like me who works from my imagination, don’t play me a piece of music and tell me you want something like that, even if it’s my music (laughs).

Sometimes I’d say “please show me the film without a temp track. I want to see it with just the dialog. I don’t want to hear music.” So, then I can imagine the music and that became less and less possible to do. And people say, well, why did you stop? Part of it was because I didn’t enjoy working as an imitator. That’s never who I was. I wanted to create from scratch in the sense of the music for a film. Obviously, the film exists, the visuals talk, the story talks, the characters talk. You have to listen and take it in and then see what bubbles up as a composer. But more and more, it was all about “well, here’s our temp track and we love this” or maybe “this one we don’t like so much” and it was all about trying to triangulate between what you see on the film, what music is already connected to the film, so you don’t even have that blank slate. That blank slate was not just important for me to enjoy my work, but truthfully, it was important for me to do my best work, and I think when I got pushed into a position of having to triangulate with specific pieces of music the director wanted me to hear – and it’s not the worst thing in the world as there are people that work very well that way – It was not my strength. So, I think my work wasn’t as good when I had to do that and it just didn’t feel good to do it.

You mentioned having your own music as so some of the that temp music. Did you ever have people approach you and say, “we need something Terminator-ish?”

Oh yeah and I made I really made a big deal about not doing that where I could, you know. Soon after Terminator 2, I got offered Straight Talk with Dolly Parton, a romantic comedy and I was like, “oh, yes!”. After the original Terminator, I got offered Compromising Positions, which was Susan Sarandon in a kooky comedy murder mystery based on a real story. So that was what I really enjoyed. I actually started to pull back as it’s hard not to be typecast and to this day, I had to make an attitude adjustment because everyone loves those Terminator scores, and a few other ones that really stuck with them, and I’ve just had to accept, hey – they were iconic films and I got to contribute to them and I did my job well, hopefully so that the music has moved along with the iconic-ness of the film and been accepted historically as something worth continuing to talk about.

Absolutely and I think it’s not a reach to say that a movie like Terminator wouldn’t be as impactful without the music that you created for it.

Well, thank you. So yes, those films, Terminator, Fright Night, most of the films that people remember my scores too now, were ones where I was giving given a real clean slate. Like, “here’s my movie, Brad. I’ll come back in two days. Show me what your idea is.” And that’s where those scores came from.

So, having said that, you’ve done everything from frat boys on vacation, cops on water, to robots from the future. Is there a particular movie genre that you prefer working in?

No. You know, it’s so funny because I know this may sound kind of strange, but there’s a big difference between the scores I enjoyed composing and the score and the films that I might enjoy as an audience. I was never somebody like – horror pictures, just not my thing and most of the scores I did for “horror pictures”, I never really treated them or saw them as horror pictures. Fright Night was a coming of age comedy, scary… you know, it was a full dimensional film and I really went after the humanity in it, which I think in horror films is very important, actually, because you don’t care about the characters. You don’t care if they go into the basement. (laughs)

So I always wore my musical humanity on my sleeve and if I had to make this big thing that made you jump in your seat, I would do it but that wasn’t my main orientation. There isn’t a particular genre; the genre of films that I really love as an audience don’t necessarily have a lot of room for score to express. A really good dramatic film, unless it’s a big period, sweeping period piece. But if it’s really about human beings, which I really enjoy as an audience, films that explore the human condition and all that, they’re not necessarily musical muscle flexor type palettes. They’re not canvases where a composer can go in. So, I’ve really enjoyed the films that have space and where the directors leave space for the music. There are certain directors I’ve worked with where you watch it and you go, “Oh, OK. He gave me this. This is for me”. There are many that don’t have that kind of patience, so they’ll just cut, cut, cut, cut, cut and they’ll suck all the air out of the film and that air is where the music could actually make its biggest contribution.

Have you seen films and you’ve sat there thinking “I wish I’d scored that and I would have done that so much differently” or do you remove yourself from that mindset?

I remove myself because, you know, before I was a film composer, I was a film buff. I love movies, not like a film buff where I can tell you all the casts and directors, not a film buff nerd. I like to escape, especially when I was younger. You know, you never know what your kids are doing, but in junior high, I was sitting watching old movies and it might look like I was depressed from junior high -which was partially true – and it made it look like I was escaping real life -which was also partially true- but it was actually my course of study for my career. (laughs) Who knew that then right? I didn’t sit there going “Oh I want to to do that; I want to write the music for those films”. I just enjoyed that.

So as a fan of film, are there any from the new breed of composers that really stick it to you?

As far as I’ll let myself go, is to sit and I might turn to my wife and say “The closer did a great job on that”. Sometimes I’m thrown off, but not that often because I really don’t want to go there. You know, I don’t want to critique a score. Then I’m not in the story at all so that doesn’t serve me. I continually like some scores at John Williams has done that are not the Star Wars scores, that are really like good. Even as composers we have to remember that we’re often pushed into a genre and asked, in a sense, to repeat ourselves. Thomas Newman, I’ve always really loved his scores. He has a certain kind of tastefulness and also can do a wide range if people let him. There’s a young guy now named Bear McCreary who’s doing all the Outlander stuff. I think he’s really got it. You know, he understands how to incorporate all those different elements and have the score really support the story without screaming “look what I can do”.

You are speaking to us from your studio. How has the setup changed since you began? I’m assuming you’re doing a lot more in the box stuff and not as much outboard gear…

It’s so funny; this room, which is a composer studio. There’s no booth. So, you know, if I’m recording vocals, everybody’s on headphones. There’s a big screen at the front and there’s a projection from the back and to the side there’s a couple of doors that lead to a whole space on the other side that used to be the machine room. So, it used to have the twenty-four track, all the noise reduction, the four track, it was very noisy. So, we have we closed it off and for years that’s not been in use and it’s been kind of closing and closing to the point right now, I finally felt guilty about the wasted space and made a little apartment over there and one of our friends is living in it right now as it’s a separate building from the main house. But yes, the whole studio right now or ninety nine percent of it is in my iMac, which is crazy. Given that I started at a point where on those Fairlight’s that I did T2 on, to get an external hard drive was like $8,000. It was as big as ten toasters tied together and I believe it was 120mb.

So yeah, it’s really crazy where it’s gone, and I think it’s great in the sense that people can make a record in their bedroom, and it sounds pretty damn good. There’s a technological growth that has, I think, democratized film scoring as well, because the studio that I built, I had this vision of being able to work at home without watching the clock and a $350/hour studio. And I had that other people, too. In the early 80s, even before Terminator I realized I wanted to be able to work in my own space for at least my most experimental creative part, then when we you added a bunch of other musicians, we went and took my twenty-four track tapes to somewhere else. But I had to invest close to $400,000 to be able to make a score like the Terminator in my own studio. Both Terminator two were top to bottom done in my own studio. Now, I don’t know exactly what it would cost, but I would think that you could do it for under $10,000.

Although I suppose conversely, had you had the technology that you have now, back then, you wouldn’t have had to use it like that. You know, that happy mistake…. You’d have MIDI now, you’d have almost zero latency, quantization etc., so those sorts of things wouldn’t have occurred.

I have no regrets. I think I was really lucky. You know, in the early 70s, I had one of the prototype Moogs because my dad was a music teacher and his friend was assisting Robert Moog in upstate New York. So, I had one of the first synthesizers that I could play around on. And everything that’s happened in my lifetime, it’s just amazing to think through the developments in keyboards, the developments in recordings, and hopefully like everything else in the world we use them for embellishing the humanity that we all share, as opposed to what we’ve done with a lot of technologies, which is basically moving towards destroying the planet. Of course, the Terminator films, Jim was looking at artificial intelligence and the dangers of it. I still don’t think we’re really on top of that situation. You know, just like we’re not on top of messing with genes and all that sci fi stuff, and here we are in a pandemic. It’s like a bad sci fi film, but it’s happening now.

Once we return to normalcy, assuming that ever happens, what’s on your slate after Full Circle?

I’m going to make a little pitch about Full Circle here. I really, really appreciate the interest in all my past work, and it took me a while because I wasn’t that into social media, but I started to get glimmers a number of years ago that people were actually out there listening to things that I had done, which were just jobs that I did and moved on to the next one, that they actually were meaningful to people. So, my pitch is for artists in general, to take your respect of them from their past work and open your mind and ears and eyes to who they are in the present if they’re offering. So, I’m offering Full Circle, no charge just to share. My goal was just to share this present work because I think it’s a very human work and funny and scary and got all the dimensions, hopefully. I’m hoping that just some portion, at least of all the Terminator and Fright Night fans will say, “Hey, if I really loved that, maybe it’s worth checking out”. And there may be a lot of people where it’s not their cup of tea. So, I guess to answer your question coming out of that pitch, which is please, everybody, I have this goal to share this with as many people as possible and make me feel really good if you guys just check it out, so it’s not just something I did in my cave that nobody knows happened. (laughs)

Going on to the future, that’s basically the challenge. The challenge is to use this platform of work I was privileged to do and iconic projects I was privileged to be attached to, and as an artist, to hopefully get supported. And I’m not talking about financially – I’m talking about audience wise. To feel supported, to keep creating. Because there’s a number of things I created between my last film score and Full Circle. Borrowed Time was probably only experience live by under a thousand people, as the various the shows I did were in smallish venues. This thing (Full Circle) I’ve been working on for over ten years and virtually aside from the cast, and maybe a few friends and family, nobody’s experienced it. So, I would like to keep the energy going as an artist and see what I have inside me to create and I’m hoping there’s an audience for it.

Thanks so much for taking time out to chat with us and all the best with Full Circle.

Thank you guys; these were some good questions!