When people talk about big companies, two terms pop up again and again: parent company and subsidiary. On paper, they look tidy enough, yet the way they play out in real life can feel more like a family dynamic than a spreadsheet. Nakase Law Firm Inc. often receives questions from business owners asking, how does a subsidiary differ from a parent company in corporate structure?, and the clearest answers usually mix a bit of story with the nuts and bolts.

Before we get too far, a quick detour helps. California Business Lawyer & Corporate Lawyer Inc. frequently explains to clients what is a corporation, and how does it differ from an LLC?, and that foundation makes the parent–subsidiary picture click into place for a lot of folks.

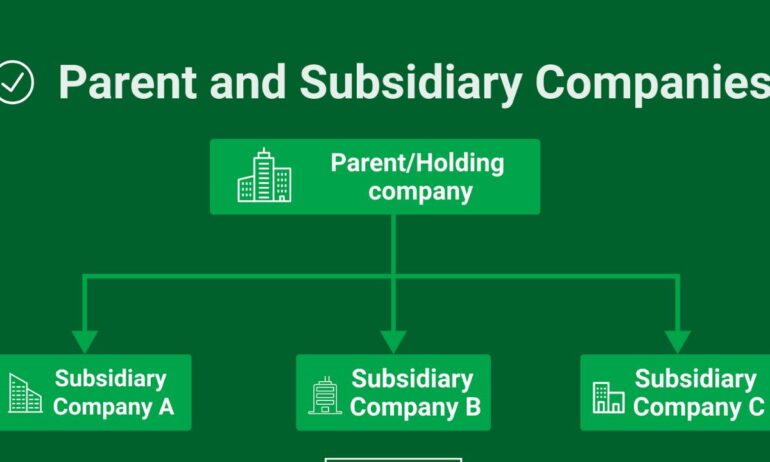

A quick picture to start

Think of a parent company as the head coach and the subsidiary as a team that plays under the same banner. The coach sets direction, funds training, and hires key staff. The team still runs plays on the field, wins or loses on its own record, and signs its own contracts. Same organization, different roles, shared goals.

What is a parent company?

A parent company gains control by owning a majority of another company’s voting stock, often above the 50 percent mark. Some parents are hands-on, shaping strategy, budgets, and leadership. Others operate like investment hubs, focusing on capital allocation and long-range plans rather than daily operations. Picture a chef who owns several restaurants: the chef designs the concept, picks the locations, and decides where to invest next, yet each restaurant has its own manager and staff.

What is a subsidiary?

A subsidiary is a separate legal entity that can hire employees, open bank accounts, sign leases, and build its own brand presence. Ownership can range from partial to 100 percent. If a parent owns the entire company, it’s a wholly owned subsidiary; if the parent owns most of it, it’s majority-owned. The setup lets companies try new markets, create focused brands, or keep higher-risk ventures cordoned off from the rest of the group.

So, where do they diverge?

Here’s a fast side-by-side, the way founders and investors often think about it:

- Ownership: the parent holds the stake; the subsidiary is the entity being owned.

- Decision rights: the parent usually keeps the final say on strategy and big money moves; the subsidiary runs the day-to-day.

- Liability: the subsidiary’s debts and legal issues are typically its own; the parent is usually insulated unless lines are blurred.

- Purpose: parents use subsidiaries to expand, test ideas, and segment risk; subsidiaries gain resources, credibility, and direction.

Why companies pick this arrangement

Risk management is a headline reason. Say a tech company launches a driverless pizza delivery venture. Housing that venture in a subsidiary can keep any claims or debts tied to that entity, not the entire corporate group. Another draw is tax planning in certain jurisdictions, where results from different subsidiaries factor into group filings. There’s also a branding angle: a parent can own multiple labels serving different customers, each with its own voice and marketing approach.

Here’s a small real-world-style example. A regional beverage company wants to sell a trendy energy drink to college students, yet its flagship brand speaks to families. Rather than confuse its main identity, it forms a new subsidiary to launch the youth-oriented product. If the new drink takes off, the group celebrates. If it stalls, the main brand stays steady.

The legal layer that keeps the walls up

The corporate world relies on separation between entities. Even within the same group, each company keeps its own books, bank accounts, and contracts. Courts honor that separation when companies maintain proper distance. If a parent treats a subsidiary like a mere extension of itself—same bank account, sloppy records, no independent decision-making—the shield can crack. That’s rare for well-run groups, yet it’s a reminder to keep the corporate housekeeping in order.

Familiar names that use this setup

Plenty of household names follow this playbook:

- Alphabet Inc. serves as the parent for Google, YouTube, and Waymo.

- General Motors owns entities for different vehicle lines, such as Chevrolet and Cadillac.

- Procter & Gamble operates a portfolio of brands, each with its own presence on store shelves.

A quick grocery-aisle moment brings it home. You might grab Pampers and Old Spice on the same run and not notice they report up to the same group. Different labels, shared ownership.

When a subsidiary makes the most sense

A few typical triggers stand out:

- New geography: entering a country with unique rules and taxes.

- New audience: launching a brand with a tone that wouldn’t fit the parent’s image.

- Risk ring-fencing: containing a higher-risk product line so bumps don’t shake the whole group.

- Asset protection: placing valuable intellectual property in a dedicated entity with its own licensing.

Here’s a founder-level story you might hear over coffee. A small software company lands a contract with a hospital network. Healthcare brings strict compliance, so the founder forms a subsidiary to handle that line of business. The new entity hires staff trained in medical privacy and runs audits suited to the field. The core company keeps selling to regular clients, and the healthcare work lives inside its own structure, with its own controls.

The parts that can get messy

No structure is magic. Parent–subsidiary groups face a few recurring snags:

- Compliance complexity multiplies once you cross state or national borders.

- Leadership friction can pop up if a subsidiary team feels micromanaged.

- Financial reporting at the group level can blur which unit is thriving and which needs a tune-up.

A practical fix many CFOs use: clean intercompany agreements, clear service-level expectations, and dashboards that show both consolidated results and each subsidiary’s metrics. It isn’t glamorous work, yet it keeps surprises to a minimum.

A conversational recap

So, does a parent company “run” a subsidiary? In big calls, yes; on everyday choices, the subsidiary’s team usually leads. Are they the same company? No—their legal identities are separate, which is the point. Can the walls come down? They can if records and behavior erase the distinction, so good process matters.

What this means for owners and teams

For a founder, the structure can open doors. You can test a bold product or expand into a regulated field without putting the full company at stake. For an investor, subsidiaries provide clearer buckets for risk and return. For employees, the setup can create focused cultures: a startup-speed unit for one market and a steadier, process-driven unit for another, all under a single umbrella.

Here’s a quick kitchen-table example: a family-owned bakery grows into catering, frozen goods, and a café concept. Each line has different rhythms, costs, and hazards. By placing each line in its own subsidiary, the owners see which one truly pays the bills, which one needs a push, and which one should stay small and local. The group gets clarity without losing the benefits of shared suppliers and marketing.

Bringing it all together

Parent companies and subsidiaries form a flexible system that mixes direction from the top with execution on the ground. Parents fund, plan, and set guardrails; subsidiaries build teams, serve customers, and carry their own obligations. The design isn’t just for giants—it can help a growing business try new ideas, protect its core, and speak to different audiences without muddling its voice.

One last thought for anyone sketching an org chart right now: pick the structure that matches the risks you’re taking and the story you want your brands to tell. Keep the records clean, give each company room to operate, and you’ll see the benefits of the setup in everyday decisions—budget meetings, hiring plans, and product launches—not just at tax time.

ALSO READ: 5 Reasons Hiring a Local Property Manager is Good Business